Very few Latin@s in the Christian faith know the importance of small town Ruidoso, New Mexico. There, in a little hacienda in the late 80s, a group that would become some of the leading Latin@ voices in theology and biblical studies made a choice that changed the Brown Church for the next thirty years. The scholars gathered to imagine a new theological association for Latin@s. They discussed the challenges facing Latin@ immigrants to the US and the faith experiences of their people. Nestor Medina had the opportunity to interview Orlando O. Espín, a participant at this gathering, and he summarized the group’s decision by writing: “Aware of their differences and of the wrong perceptions they had of each other’s communities, they decided to downplay the differences that divided them and instead emphasize the suffering and marginalization they had in common” (emphasis added).

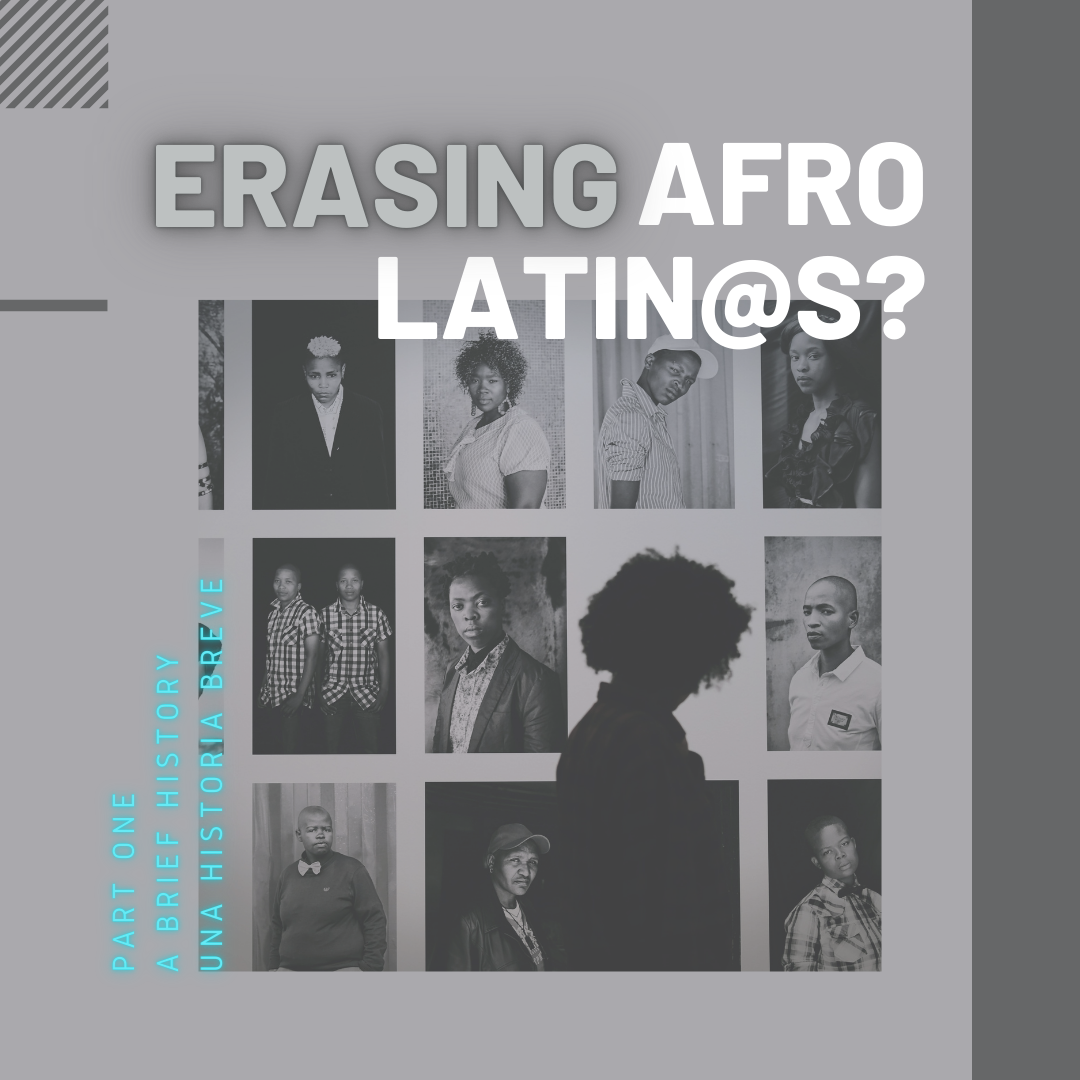

Downplay the differences. Emphasize the common struggle. This became the standard style for Latin@ theology in the US. To downplay the differences, the group of scholars adopted mestizaje as a central hermeneutic for understanding Latin@ identity and experience. Three decades later, theologians are asking if flattening the differences between Latin@s made certain struggles – like that of Afro-Latin immigrants who face the “double punishment” of anti-immigrant and anti-black bias – more difficult to overcome. By disaggregating the category “Latinos,” these younger academics reveal the greater challenges facing Latin@s made invisible by the homogenizing work of the past. Many today argue for a dispersion of Latin@s into smaller, specific designations rather than larger monolithic categories. Perhaps it can be said that Latin@s need the scattering of Babel. It’s time we speak in different languages.

For many, the Tower of Babel is a story of curse and punishment. The people in the story gathered to build a city and a tower to reach the heavens. After reviewing their project, the Lord thwarted their work by changing their tongues. Unable to speak to one another, the people scattered across the earth. It is common for this reading of Genesis 11 to be accompanied with a reading of Pentecost (Acts 2) as the reversal of Babel. In Genesis, God cursed the people into language diversity; in Acts 2, the Holy Spirit makes people understand one another. Several biblical scholars have challenged this reading of Babel and Pentecost, and it is important to reconsider these stories in light of the question of Latinidad. How are Latin@s one together? Must our oneness equal sameness? Must we focus only on our commonalities while ignoring our differences? How might a rereading of these stories provide a new biblical vision?

Eric Barreto points to the particulars of Acts 2 to note the disconnect between it and Babel. If God intended to reverse a curse, would God not have caused the people to speak the same language? Instead, the Holy Spirit causes those diverse speakers to hear and understand the good news in their own tongue. Language diversity remains intact. Therefore, it seems unlikely that God intended language diversity as a punishment, and the Holy Spirit does not appear to be undoing such diversity. If Acts 2 honors the diversity of languages, how does that change the way we read Genesis 11?

Pablo R. Andiñach proposes that we read the story of the Tower of Babel as an anti-imperialist story. He observes in the story an ironic use of the name Babel that relies on similarities in different languages. In Akkadian, the city is named Bab-il, which means the “door of God.” This was the short form of the full word, babilani¸ “the door of the gods.” A careful reading of Genesis 11 notes the motivation credited to the builders of the city. They wanted to make a name for themselves (v. 4). These builders, says Andiñach, were attempting to establish their supremacy by declaring their city as the gateway to the gods. Their city was to be the city, and their empire was to be endorsed by the gods connected there. It was their intention to establish this city as the seat of power. Already, Genesis 11 foreshadows the hegemonic vision of domination embedded in Babylon. The Hebrew writers mock this city when they write that God scattered the builders, and it is for this reason the place is now named Babel (Hebrew: confusion). God renames. God does not choose Babylon, nor does God permit the imperialists to absorb all peoples into their kingdom. The empire has been confused, scattered, left in disarray. What does this mean for language diversity?

“Destroy, O Lord, divide their tongues; for I see violence and strife in the city.”

Andiñach argues that language control, like the naming of a place, city, or people, is tied to power. Babylon is the biblical name for the empire, one which Israel would later enter as prisoners of war. The Israelites would one day be forced to speak the language of the empire, forced to live under the cultural hegemony of its oppressors. Genesis 11 is a foreshadow of God’s intention for Babylon. God condemns Babylon’s supremacy claims. God scatters the empire, and in doing so, God privileges those the Babylonians would eventually oppress. The story indicates God’s intention for the world. God does not want monolithic absorption into the empire’s ways of being. Instead, God forced the peoples back out to continue to fill the earth with teaming and flourishing. Language diversity is what God intended for the world. Babel was dismantled because it threatened God’s intended order. The rest of the Hebrew Bible cyclically shows God destroying Babylonian echoes; wherever monolithic violence is the dominant form of being, God dismantles it.

We must be cautious about how we judge the Latin@s of the past as they faced the empire’s monolithic violence. In the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, the US was operating an assimilationist vision for racialized minorities. This vision dates back even further to the early 1900s, as Daniel Burnham and other prominent city planners imagined field houses where immigrants would be taught the “American way of life.” These field houses would also host language classes, and it was Burnham’s vision that immigrants be required to attend these classes. This vision didn’t fully materialize in Chicago, Burnham’s city, but the spirit of this planning continued in similar political programs. The goal was to produce one way of being, according to the logics and visions of white leaders in power. In the face of assimilation programs like these, the scholars of the past resisted by naming themselves and honoring their own traditions and cultures. The protection of identity and culture is, in part, what drove the Latin@ scholars meeting in Ruidoso to collaborate. To understand their decisions, they must be reviewed against the Babylonian operations of the US.

Latin@s and Asian Americans

As mentioned earlier, the hacienda meeting is the origin of mestizaje as a significant theological tool for Latin@s in the US. Those present chose to use Virgilio Elizondo’s work as a central hermeneutic for understanding the Latin@ experience. To this day, mestizaje remains the dominant way of understanding Latin@ identity. We are the mixed people of the borderlands. Those who are ni de aquí, ni de allá (not from here or there). We are, according to the logic of mestizaje, neither white nor black; we are “brown.” Mestizaje presented the possibility to speak of our in-betweenness. The usefulness of the identity marker was its gathering power. Latin@ theologians from Cuba, Mexico, the US, and Puerto Rico could now speak as one “mestizo” people. They could live under one name.

This decision is not strange for its time. In the late 60s, student activists in California went on strike for an ethnic studies curriculum. In an interview for Asian Americans Generation Rising, Penny Nakatsu says she heard the term “Asian American” for the first time in 1968 while attending these strikes. The 60s and 70s were a time of coalition building, of gathering people from diverse nationalities under a single name. With their larger numbers this group could apply political pressure to get their needs met. Like the Latin@ theologians, Asian American students were most concerned about the shared suffering and marginalization of their peoples. They gathered to resist a common oppressive regime.

In 2021, Asian American, Latina/o, Hispanic, and other similar designators are contested by politically active students and scholars who share the motivations of their counterparts in the 60s and 80s. Today’s activists use a greater diversity of identifiers with the expressed desire of advocacy for unseen groups. This commitment is an echo of the past, but many in this younger generation believe the terms of the past are too homogenizing. Too monolithic. Among Latin@s, some even accuse the scholars of the past of essentializing the Latin@ identity. Essentialism is the inflection point. Yet the turn to more specific identities may not solve the essentialism problem. In a video about the erasure of black Latinas from reggaeton music videos, La Gata suggests we reinstate the brown paper bag test to ensure sufficiently dark Afro-Latinas are cast; Afro-Latinas with the potential to “pass” are her concern. In a desire to do justice, she risks essentializing Afro-Latinidad around the boundaries of pigment.

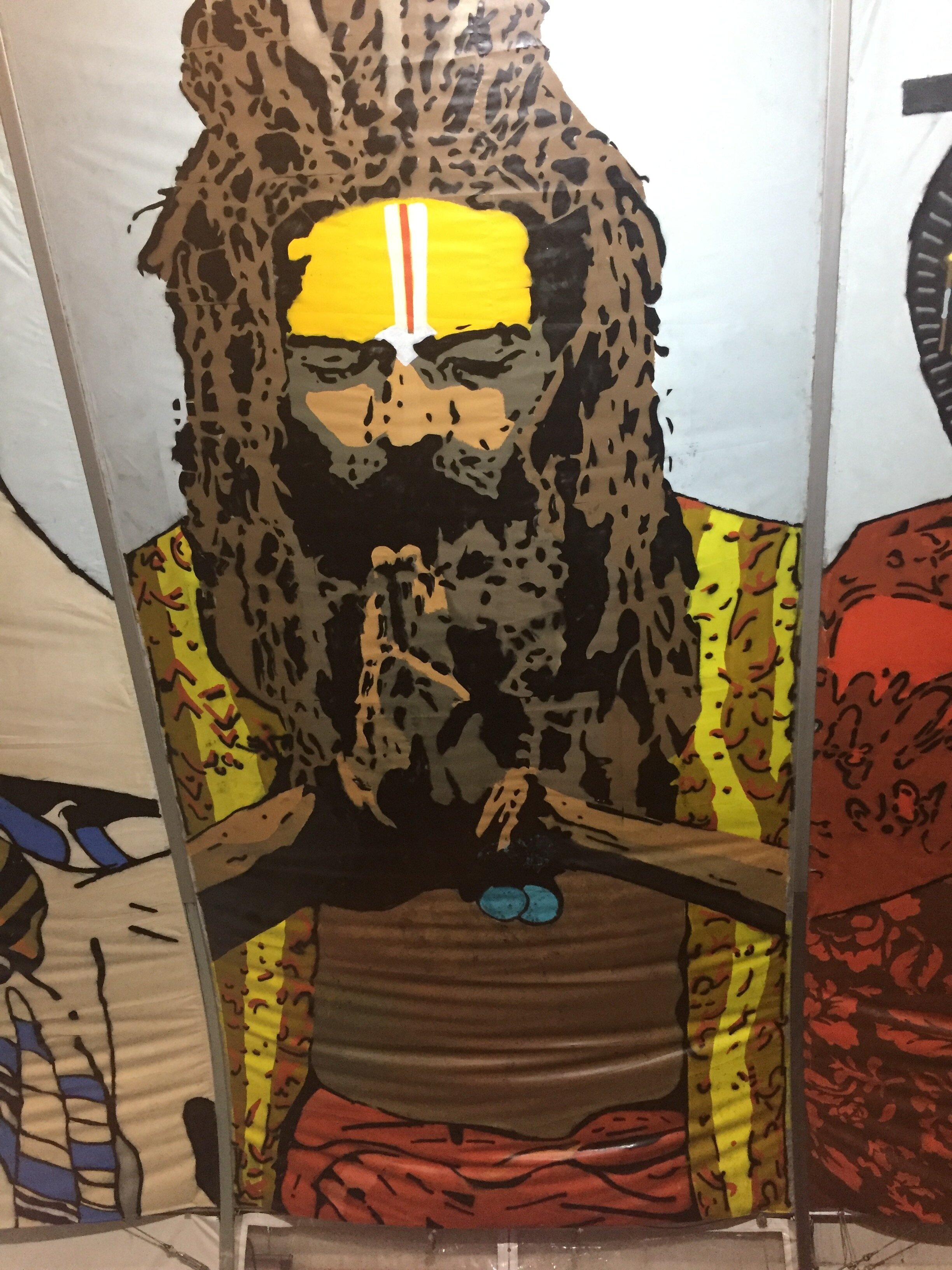

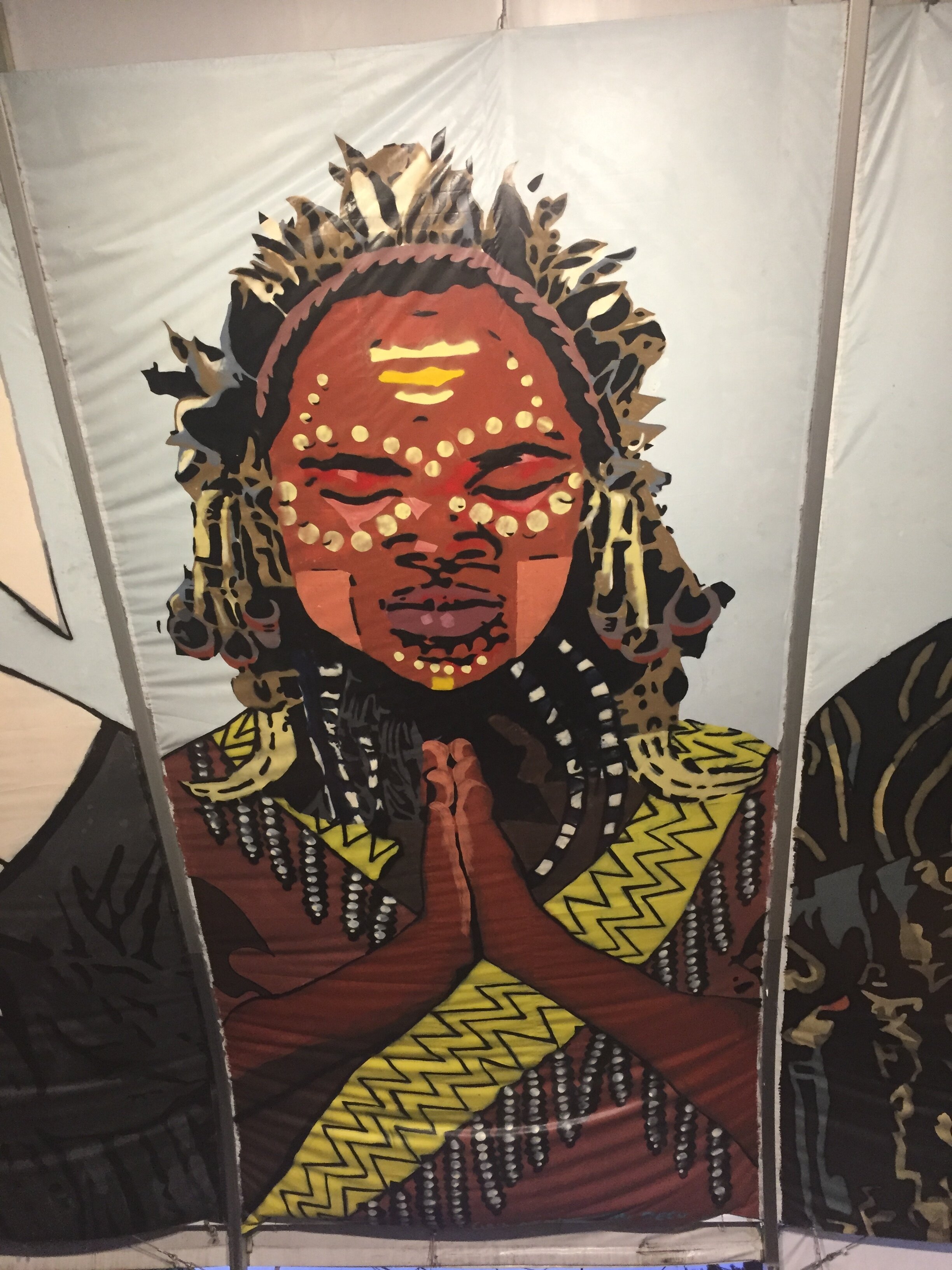

Missed in the tension between generations is the origin of the essentializing/naming problem. The marginalization of distinct groups in the 60s, which demanded a gathering response, and today’s homogenizing of minorities into a single “othered” group, which demands a scattering response, are both operations of white supremacy. These machinations are part of what Emilie Townes refers to as the fantastic hegemonic imagination of the US. “The fantastic hegemonic imagination traffics in peoples’ lives that are caricatured or pillaged so that the imagination that creates the fantastic can control the world in its own image.” The fantastic is not limited to works of art, marketing, or media. Townes argues that images of and about minoritized peoples shape the very fabric of the everyday. Yolanda M. Lopez reveals this most vividly in her 1994 art installation The Nanny, from the Women’s Work is Never Done series, in which she sets the uniform of a nanny, often worn by Latinas, between two marketing posters depicting white women exploiting Latinas. The marketing, in this case a tourism ad and a wool fabric promotion from Vogue magazine, continues to perpetuate an imagination that negatively shapes material conditions for the most abject.

Artworks like The Nanny demonstrate what Townes calls the cultural production of evil. The ads, uniform, and other elements of the installation demonstrate the way little everyday things perpetuate evil imaginings of minoritized peoples; they maintain the fantastic hegemonic imagination. The ubiquity of things that perpetuate this imagination ensures that everyone internalizes it. Townes again: “It is found in the privileged and the oppressed. It is no respecter of race, ethnicity, nationality, or color. It is not bound by gender or sexual orientation. It can be found in the old and the young. None of us naturally escape it, for it is found in the deep cultural codings we live with and through in US society” (emphasis added). How, then, do we avoid the cultural production of evil that consistently marginalizes whole collections of diverse peoples? How do we resist the fantastic hegemonic imagination and its tendency to group, name, and define people according to its own image? How do the generations work together to resist the empire?

ESSENTIALISM AND WEST SIDE STORY

In the 60s, when Latin@ scholars chose to live under a single name, they did so to gain greater political power within a system that ignored them unless they assimilated. The system, however, turned their gathering efforts into a tool in the fantastic hegemonic imagination, and it was used to perpetuate visions of Latinidad that further marginalized the people it named. This is perhaps most evident today in Spielberg’s recent remake of West Side Story. During a recent panel discussion with leading Puerto Rican scholars, Grammy-nominee Bobby Sanabria shared about his involvement on an advisory board that consulted Spielberg, Tony Kushner, and their team on the cultural issues to consider for their remake. Sanabria explained that the original film resonated with him personally because he remembered having to join a Puerto Rican gang in the 50s “to protect ourselves from the white gangs that didn’t ‘dig us’ too much…” He continued, “it’s a reality that happened and is still a reality today.” Brian Eugenio Herrera, another panelist, pushed back, noting that the reality of gangs was and is certainly true, but the impact of West Side Story is that it filled the US imagination with images of Caribbean Latin@s as criminal gang members.

The image produced by the film is not of gang life as self-defense but rather gang life as violent criminality. Over the 60 year period since the release of the original film, young Afro-Latinos have resisted this perception. What had been impactful for Sanabria was poison for the next generation. The problem, as explained by Herrera, was the development of an aesthetic archetype, a permanent caricature of what it means to be Puerto Rican. The film may have portrayed something specific to its time, but this image became the universal, essential description of Latino youth even beyond Puerto Ricans. With the release of this remake, the question of essentialism returns to the fore.

RESISTING THE AESTHETIC ESSENTIALISM OF BABYLON

The debate about West Side Story runs along the grain of the generational tensions already described here. An older generation praises the film; a younger generation resists it. Some within the older generation perceive positive power in it. A younger generation feels debilitated by it. Herrera rightly notes that the film, like the scholars of Ruidoso, set the style for what it means to represent Latin@ people. The scholars of the hacienda in Ruidoso also set the theological style for Latin@s, adopting mestizaje as their tool to downplay their differences. To resist the empire today, however, perhaps what we need to do is release the hegemonic controls of style and aesthetic. Again, we need the grace of Babel and the affirmation of Pentecost.

Victor Anderson, Professor of the Program in African American and Diaspora Studies and Religious Studies at Vanderbilt Divinity School, observes a similar generational tension in the work of his black students. According to Anderson, students continue to ask questions he thought were resolved by the previous generation of scholars. Questions like, “What makes one black? Must black scholarship be political? Are black films, literature, and arts anything produced by a black person? To what extent may black scholars embrace multiculturalism as a mode of difference and remain distinctively black? Is not there something about being black that is shared with no other race?” These questions echo contemporary questions about Afro-Latinidad and Latin@s more generally.

Instead of essentialized styles that restrict the identity to one form, Anderson proposes that black scholars conceive their work as expressions of the manifold manifestations of blackness. For Anderson, blackness should be understood as an “unfinished state” and a “complex subjectivity.” By unfinished state, Anderson is suggesting that the final, definitive word on black identity remains unsaid. Each new generation contributes to the shape and formation of black identity; they add another manifestation to the manifold. Complex subjectivity is an acknowledgement that each person within a group is multi-site, connected to other worlds that shape their identity. As Emilie Townes puts it: “we do not live in a seamless society. We live in many communities – often simultaneously.” Together, the ideas of these scholars point to a post-Babel world that affirms the desires of both generations and opens to a diversity of peoples.

The story of Babel and Pentecost reflect God’s affirmation of a diversity of peoples. Again, Babel is not a curse into diversity, nor is Pentecost a reversal into homogeneity. In both stories, God affirms the minoritized other and does so in contrast to the empire. (Pentecost serves as an early encounter between the Church and Rome.) How do we reconcile the two generations and avoid the essentializing tendency of Babylon? There are at least three lessons presented by the scholars discussed here.

1) Resist the fantastic hegemonic imagination inside us

Emilie Townes stressed the real possibility that the hegemonic imagination can be internalized. This is just as true for the older generation as it is for the younger. Is it possible that the older generation failed to see the inherent essentialism in their advocacy? Yes, of course. However, to critique them without acknowledging the ways they resisted hegemonic forces of assimilation in their own day is to reduce their story. Is it possible that contemporary discussions about Afro-Latinidad risk essentializing blackness in Latin@ communities? Again, yes. But, to ignore the ways black experience was made invisible since mestizaje became an archetype would align us with the empire’s tendency to erase and assimilate. All peoples are non-innocent regarding the empire. To remember the Latin@ story in detail, that is part of our resistance. To acknowledge what inspired students in California to adopt “Asian American,” to remember why Latin@s adopted mestizaje, to remember why their differences were less important than their shared struggle, this is what’s required if we are to collaborate against the empire’s operations.

2) Celebrate “Complex Subjectivity” as the grace post-Babel

While trying to explain her womanist theo-ethics, Emilie Townes writes, “life and wholeness (the dismantling of evil/the search for and celebration of freedom) is found in our individual interactions with our communities and the social worlds, peoples, and life beyond our immediate terrains.” The point is that diversity does not equal a society without seams. Diverse communities, however distinct, continue to have points of intersection. And, as Townes says so well, wholeness demands we work within our distinct group and with others beyond our tribe. We can delight in and celebrate the gift of Babel, the gift of diversity in language and peoples, while still connecting along the seams of connection. To say it differently, we can now celebrate the differences instead of downplaying them. This celebration should parallel our continued work against our common struggle. Celebrate difference. Resist the common struggle. That should be the formula going forward.

3) Work in the Everyday (lo cotidiano)

For Latin@ and Black scholars, the everyday is the location for resistance. The artwork of Yolanda M. Lopez reminds us that the fantastic hegemonic imagination of the empire produces everyday objects of evil. So, our resistance must also operate in the everyday. Everyday we must be attuned to the ways our imagination is being shaped, and everyday we have an opportunity to make otherwise worlds. As non-innocent, complex subjects who live together in the grace of God’s work in Babel and Pentecost, we can create virtuous cycles of cultural production that set people free to live into their language and identity. Everyday arts, everyday products, everyday words can liberate people from the monolith. Everyday rituals can point people to the Word that judges Babylon and sets its captives free to testify of His goodness in their tongue and tribe.

About Emanuel (Ricky) Padilla

Emanuel Padilla is president of World Outspoken, a ministry preparing the mestizo church for cultural change. Emanuel is committed to serving bi-cultural Christians facing questions of identity, culture, and theology. He also serves at The Brook, a church on the northwest side of Chicago, along with his wife Kelly.

Follow him on Twitter to learn more.

Articles like this one are made possible by the support of readers like you.

Donate today and help us continue to produce resources for the mestizo church.